-

Adrian Berg RA (1929-2011)

-

James Butler MBE RA RWA FRBS (1931-2022)

-

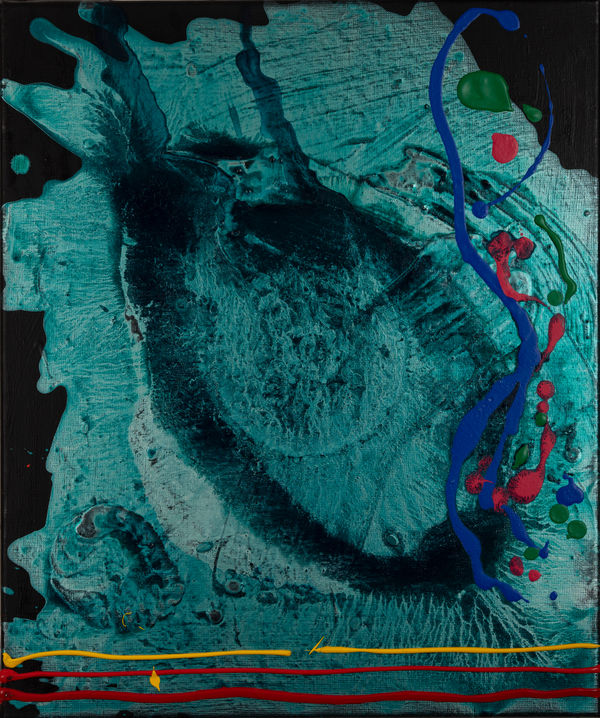

Prof John Hoyland RA (1934-2011)

-

Prof Maurice Cockrill RA (1936-2013)

-

Albert Irvin OBE RA HRWA (1922-2015)

-

FREDERICK GORE CBE RA (1913 – 2009)

-

Angie Butler

-

Dame Barbara Rae DBE RA FRSE

-

John Bellany CBE RA HRSA (1942-2013)

-

David Mach RA

-

Philip Sutton RA